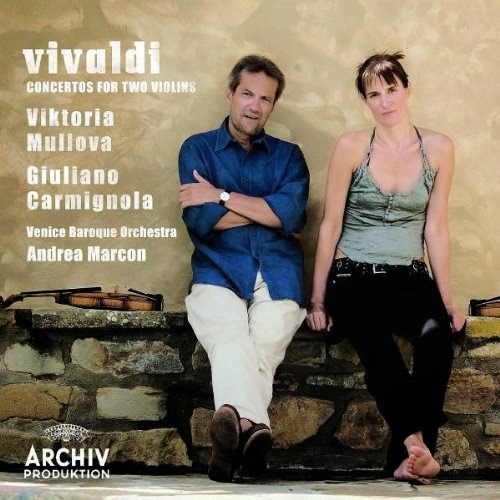

Viktoria Mullova / Giuliano Carmignola VIVALDI Concertos for two violins

Thanks to The Four Seasons, the solo violin concerto is the genre with which Vivaldi is associated above all others. And indeed, at nearly 250 works, this species of composition forms the largest single portion of his output, outnumbering his next favourite, the concerto for orchestra, by more than four to one. In historical terms, too, his development of the formal aspects of the solo concerto was his greatest legacy: his model of three movements in the sequence fast-slow-fast still wields influence today, and the so-called "ritornello" structural principle - in which returning orchestral statements of a strongly defined, harmonically stable main theme offer a framework for more free-ranging and lightly scored passages involving the soloist - informed every composer's approach to concerto-writing until well into the 19th century.

Yet Vivaldi's concerto output is considerably more varied than that. Not only did he compose concertos for a wide range of string, wind and brass instruments, he also wrote them for differing numbers of soloists, from none to 13. His first taste of international fame, indeed, came with a set of twelve concertos which offered alongside its four solo concertos equal numbers of concertos for four and two violins. Published in Amsterdam in 1711 under the title L'estro armonico, it achieved great popularity in northern Europe in those early days of the instrumental concerto, making its mark on German composers in particular. The flautist and theorist Johann Joachim Quantz later recalled that "as musical pieces of a kind that was then entirely new, they made no small impression on me. I was eager to accumulate a good number of them, and Vivaldi's splendid ritornelli served as good models for me in later days". Vivaldi also acquired a keen following at the Dresden court, who sent their best violinist Johann Georg Pisendel to Venice to study with him; and in Weimar the young J.S. Bach transcribed for solo keyboard six pieces from the 1711 set, including two of the "double concertos".

Only two further concertos for two violins by Vivaldi were published in his lifetime (one as part of his op. 9 La cetra set in 1727, another printed independently in Amsterdam), but there are a further 24 surviving, most of them in the huge manuscript collection of Vivaldi's works now held in the National Library in Turin. These concertos are rarely performed today, either in concert or on record, but, like much of Vivaldi's unpublished output, contain music that is not only undeserving of its neglect, but offer facets of his creative personality that are not always evident in the works he chose to see into print.

The concertos presented on this disc by Viktoria Mullova and Giuliano Carmignola demonstrate for the most part Vivaldi's usual method of writing for two soloists on similar instruments: rapid interchanges of phrases and melodic fragments which echo, overlap and swap over with each other, alternating with passages of parallel motion, almost invariably euphonious (only the slow movement of RV 523 uses the texture to create expressive dissonances). They thus differ from the Vivaldi-inspired but more polyphonic manner of Bach's well-known Concerto for Two Violins, and show the influence of the dominant texture of the chamber music of the time, the trio sonata, in which two matched instruments would duet over a continuo accompaniment consisting of a bass-line instrument and a chord-playing lute, harpsichord or organ. This similarity appears even more obvious in the slow middle movements of RV 509, 516, 523 and 524, which feature "continuo" instead of orchestral accompaniment, and becomes explicit when it is seen that RV 516 shares both its second movement (with slight differences) and much of the material of its first and third with one of Vivaldi's unpublished trio sonatas (RV 71).

Whether these dialogues be virtuosic (as in the outer movements of RV 511 and 514) or melodious (as in the relaxed first movement of RV 509 or the expressive second movement of RV 514), they almost always give meticulously equal treatment to the two soloists, with neither assuming a dominant role in terms of range, technical difficulty or quantity of material. The effect is of a single character in the solo role, albeit one performing musical feats more complex than those achievable by a single player. In this regard it is easy to imagine them providing performance material for the youthful musicians of the Ospedale della Pietà, the Venetian orphanage of whose renowned all-female orchestra Vivaldi had charge as teacher and director for much of his career. Their concerts drew visitors in numbers to the Ospedale's chapel on the Riva degli Schiavoni - to admire the music of course, but also sometimes to search for wives; opportunities to show off the abilities of talented players in solo roles in as democratic a manner as possible must have been welcome. This primarily local use is suggested by the fact that while all of the concertos recorded here can be found in the Turin manuscript, thought to represent Vivaldi's own personal stock of scores, only RV 523 survives in a second contemporary copy.

Occasionally, however, there are breakaways from this two-as-one approach, when one violin will play a snatch of melody while the other accompanies. Such moments are fleeting, but can be all the more striking for that, as in the final movements of RV 524 and, most memorably, RV 516, where a glorious tune emerges from the arrow-like orchestral scales of the ritornelli. Having already pictured a pair of Ospedale inmates sharing the more equal dialogues elsewhere, is it going too far for us to speculate that Vivaldi himself, known as a virtuosic if sometimes unpolished violinist, might have taken one or other of these roles, either advertising his presence as melodic lead or gently supporting a favoured pupil with rock-solid arpeggios? (Lindsay Kemp)

Yet Vivaldi's concerto output is considerably more varied than that. Not only did he compose concertos for a wide range of string, wind and brass instruments, he also wrote them for differing numbers of soloists, from none to 13. His first taste of international fame, indeed, came with a set of twelve concertos which offered alongside its four solo concertos equal numbers of concertos for four and two violins. Published in Amsterdam in 1711 under the title L'estro armonico, it achieved great popularity in northern Europe in those early days of the instrumental concerto, making its mark on German composers in particular. The flautist and theorist Johann Joachim Quantz later recalled that "as musical pieces of a kind that was then entirely new, they made no small impression on me. I was eager to accumulate a good number of them, and Vivaldi's splendid ritornelli served as good models for me in later days". Vivaldi also acquired a keen following at the Dresden court, who sent their best violinist Johann Georg Pisendel to Venice to study with him; and in Weimar the young J.S. Bach transcribed for solo keyboard six pieces from the 1711 set, including two of the "double concertos".

Only two further concertos for two violins by Vivaldi were published in his lifetime (one as part of his op. 9 La cetra set in 1727, another printed independently in Amsterdam), but there are a further 24 surviving, most of them in the huge manuscript collection of Vivaldi's works now held in the National Library in Turin. These concertos are rarely performed today, either in concert or on record, but, like much of Vivaldi's unpublished output, contain music that is not only undeserving of its neglect, but offer facets of his creative personality that are not always evident in the works he chose to see into print.

The concertos presented on this disc by Viktoria Mullova and Giuliano Carmignola demonstrate for the most part Vivaldi's usual method of writing for two soloists on similar instruments: rapid interchanges of phrases and melodic fragments which echo, overlap and swap over with each other, alternating with passages of parallel motion, almost invariably euphonious (only the slow movement of RV 523 uses the texture to create expressive dissonances). They thus differ from the Vivaldi-inspired but more polyphonic manner of Bach's well-known Concerto for Two Violins, and show the influence of the dominant texture of the chamber music of the time, the trio sonata, in which two matched instruments would duet over a continuo accompaniment consisting of a bass-line instrument and a chord-playing lute, harpsichord or organ. This similarity appears even more obvious in the slow middle movements of RV 509, 516, 523 and 524, which feature "continuo" instead of orchestral accompaniment, and becomes explicit when it is seen that RV 516 shares both its second movement (with slight differences) and much of the material of its first and third with one of Vivaldi's unpublished trio sonatas (RV 71).

Whether these dialogues be virtuosic (as in the outer movements of RV 511 and 514) or melodious (as in the relaxed first movement of RV 509 or the expressive second movement of RV 514), they almost always give meticulously equal treatment to the two soloists, with neither assuming a dominant role in terms of range, technical difficulty or quantity of material. The effect is of a single character in the solo role, albeit one performing musical feats more complex than those achievable by a single player. In this regard it is easy to imagine them providing performance material for the youthful musicians of the Ospedale della Pietà, the Venetian orphanage of whose renowned all-female orchestra Vivaldi had charge as teacher and director for much of his career. Their concerts drew visitors in numbers to the Ospedale's chapel on the Riva degli Schiavoni - to admire the music of course, but also sometimes to search for wives; opportunities to show off the abilities of talented players in solo roles in as democratic a manner as possible must have been welcome. This primarily local use is suggested by the fact that while all of the concertos recorded here can be found in the Turin manuscript, thought to represent Vivaldi's own personal stock of scores, only RV 523 survives in a second contemporary copy.

Occasionally, however, there are breakaways from this two-as-one approach, when one violin will play a snatch of melody while the other accompanies. Such moments are fleeting, but can be all the more striking for that, as in the final movements of RV 524 and, most memorably, RV 516, where a glorious tune emerges from the arrow-like orchestral scales of the ritornelli. Having already pictured a pair of Ospedale inmates sharing the more equal dialogues elsewhere, is it going too far for us to speculate that Vivaldi himself, known as a virtuosic if sometimes unpolished violinist, might have taken one or other of these roles, either advertising his presence as melodic lead or gently supporting a favoured pupil with rock-solid arpeggios? (Lindsay Kemp)

0 Response to "Viktoria Mullova / Giuliano Carmignola VIVALDI Concertos for two violins"

Post a Comment